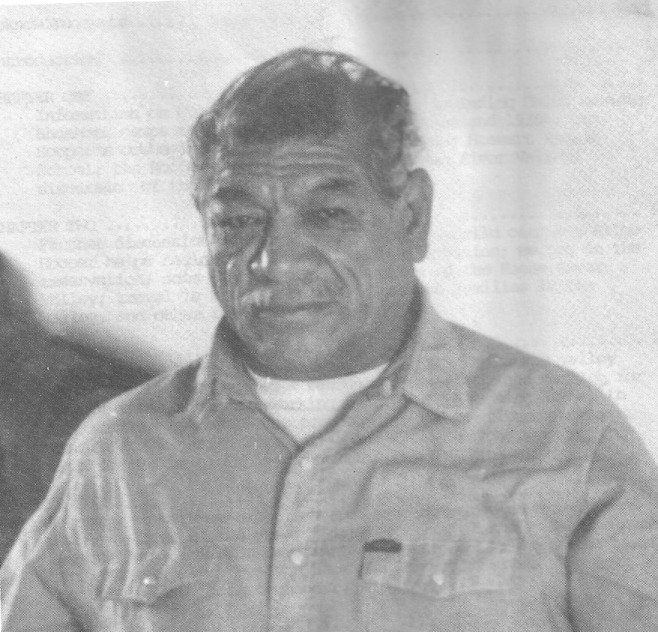

An Interview with

HOMER HOOPER

An Oral History conducted and edited by

Robert D. McCracken

Nye County Town History Project

Nye County, Nevada

Tonopah

1990

COPYRIGHT 1991

Nye County Town History Project

Nye County Commissioners

Tonopah, Nevada

89049

Homer Hooper

1990

CONTENTS

Information on Homer's family background, including Chief Kawich; Shoshone camps and native plants in the 1920s and 1930s; Art Hooper's cowboying on Monitor Valley ranches; Stewart Indian School; the Hooper family moves to the Reese River Valley; discussion of the Shoshone language.

Further discussion of the Shoshone language; wild carrots; Alice Hooper helps begin the Yomba Shoshone Reservation; moving to the reservation; some of the original ranches in the Reese River Valley; travel in the 1930s; early Shoshone families in the valley, and other families moving in.

Haying in the Reese River Valley; ranchers leaving the valley during the Depression; some ranchers who stayed, and working for some of those ranchers; working with horses; renting horses to deer hunters in the 1940s; further discussion of ranch, work; working for mines in Grantsville and Ophir Canyon; working for Basic Magnesium at Gabbs and for the Mercury Mine at Ione.

A return to work at Gabbs; an accident and subsequent health problems; some of the present-day residents of the Yomba Shoshone Reservation; diversion dams in the Reese River Valley; area health care and schooling; Western Shoshone land rights; running over the mountains and running down deer

The Nye County TOwn History Project (NCTHP) engages in interviewing people who can provide firsthand descriptions of the individuals, events, and places that give history its substance. The products of this research are the tapes of the interviews and their transcriptions.

In themselves, oral history interviews are not history. However, they often contain valuable primary source material, as useful in the process of historiography as the written sources to which historians have customarily turned. Verifying the accuracy of all of the statements made in the course of an interview would require more time and money than the NCTHP's operating budget permits. The program can vouch that the statements were made, but it cannot attest that they are free of error. Accordingly, oral histories should be read with the same prudence that the reader exercises when consulting government records, newspaper accounts, diaries, and other sources of historical information.

It is the policy of the NCTHP to produce transcripts that are as close to verbatim as possible, but some alteration of the text is generally both unavoidable and desirable. When human speech is captured in print the result can be a morass of tangled syntax, false starts, and incomplete sentences, sometimes verging on incoherency. The type font contains no symbols for the physical gestures and the diverse vocal modulations that are integral parts of communication through speech. Experience shows that totally verbatim transcripts are often largely unreadable and therefore a waste of the resources expended in their production. While keeping alterations to a minimum the NCTHP will, in preparing a text:

a. generally delete false starts, redundancies and the uhs, ahs and other noises with which speech is often sprinkled;

b. occasionally compress language that would be confusing to the reader in unaltered form;

c. rarely shift a portion of a transcript to place it in its proper context;

d. enclose in [brackets] explanatory information or words that were not uttered but have been added to render the text intelligible; and

e. make every effort to correctly spell the names of all individuals and places, recognizing that an occasional word may be misspelled because no authoritative source on its correct spelling was found.

As project director, I would like to express my deep appreciation to those who participated in the Nye County Town History Project (NCTHP). It was an honor and a privilege to have the opportunity to obtain oral histories from so many wonderful individuals. I was welcomed into many homes--in many cases as a stranger--and was allowed to share in the recollection of local history. In a number of cases I had the opportunity to interview Nye County residents whom I have known and admired since I was a teenager; these experiences were especially gratifying. I thank the residents throughout Nye County and Nevada—too numerous to mention by name—who provided assistance, information, and photographs. They helped make the successful completion of this project possible.

Appreciation goes to Chairman Joe S. Garcia, Jr., Robert N. "Bobby" Revert, and Patricia S. Mankins, the Nye County commissioners who initiated this project. Mr. Garcia and Mr. Revert, in particular, showed deep interest and unyielding support for the project from its inception. Thanks also go to current commissioners Richard L. Carver and Barbara J. Raper, who have since joined Mr. Revert on the board and who have continued the project with enthusiastic support. Stephen T. Bradhurst, Jr., planning consultant for Nye County, gave unwavering support and advocacy of the project within Nye County and before the State of Nevada Nuclear Waste Project Office and the United States Department of Energy both entities provided funds for this project. Thanks are also extended to Mr. Bradhurst for his advice and input regarding the conduct of the research and for constantly serving as a sounding board when methodological problems were worked out. This project would never have become a reality without the enthusiastic support of the Nye County commissioners and Mr. Bradhurst.

Jean Charney served as administrative assistant, editor, indexer, and typist throughout the project; her services have been indispensable. Louise Terrell provided considerable assistance in transcribing many of the oral histories; Barbara Douglass also transcribed a number of interviews. Transcribing, typing, editing, and indexing were provided at various times by Jodie Hanson, Alice Levine, Mike Green, Cynthia Tremblay, and Jean Stoess. Jared Charney contributed essential word processing skills. Maire Hayes, Michelle Starika, Anita Coryell, Jodie Hanson, Michelle Welsh, Lindsay Schumacher, and Shena Salzmann shouldered the herculean task of proofreading the oral histories. Gretchen Loeffler and Bambi McCracken assisted in numerous secretarial and clerical duties. Phillip Earl of the Nevada Historical Society contributed valuable support and criticism throughout the project, and Tam King at the Oral History Program of the University of Nevada at Reno served as a consulting oral historian. Much deserved thanks are extended to all these persons.

All material for the NCTHP was prepared with the support of the U.S. Department of Energy, Grant No. DE-FG08-89NV10820. However, any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of DOE.

--Robert D. McCracken

Tonopah, Nevada

1990

Historians generally consider the year 1890 as the end of the American frontier. By then, most of the western United States had been settled, ranches and farms developed, communities established, and roads and railroads constructed. The mining boomtowns, based on the lure of overnight riches from newly developed lodes, were but a memory.

Although Nevada was granted statehood in 1864, examination of any map of the state from the late 1800s shows that while much of the state was mapped and its geographical features named, a vast region--stretching from Belmont south to the Las Vegas meadows, comprising most of Nye County-- remained largely unsettled and unmapped. In 1890 most of southcentral Nevada remained very much a frontier, and it continued to be for at least another twenty years

The great mining booms at Tonopah (1900), Goldfield (1902), and Rhyolite (1904) represent the last major flowering of what might be called the Old West in the United States. Consequently, southcentral Nevada, notably Nye County, remains close to the American frontier; closer, perhaps, than any other region of the American West. In a real sense, a significant part of the frontier can still be found in southcentral Nevada It exists in the attitudes, values, lifestyles, and memories of area residents. The frontier-like character of the area also is visible in the relatively undisturbed quality of the natural environment, most of it essentially untouched by human hands

A survey of written sources on southcentral Nevada's history reveals same material from the boomtown period from 1900 to about 1915, but very little on the area after around 1920. The volume of available sources varies from town to town: A fair amount of literature, for instance, can be found covering Tonopah's first two decades of existence, and the town has had a newspaper continuously since its first year. In contrast, relatively little is known about the early days of Gabbs, Round Mountain, Manhattan, Beatty, Amargosa Valley, and Pahrump. Gabbs's only newspaper was published intermittently between 1974 and 1976. Round Mountain's only newspaper, the Round Mountain Nugget, was published between 1906 and 1910. Manhattan had newspaper coverage for most of the years between 1906 and 1922. Amargosa Valley has never had a newspaper; Beatty's independent paper folded in 1912. Pahrump's first newspaper did not appear until 1971. All six communities received only spotty coverage in the newspapers of other communities after their own papers folded, although Beatty was served by the Beatty Bulletin, which was published as a supplement to the Goldfield News between 1947 and 1956. Consequently, most information on the history of southcentral Nevada after 1920 is stored in the memories of individuals who are still living.

Aware of Nye County's close ties to our nation's frontier past, and recognizing that few written sources on local history are available, especially after about 1920, the Nye County Commissioners initiated the Nye County Town History Project (NCTHP). The NCTHP represents an effort to systematically collect and preserve information on the history of Nye County. The centerpiece of the NCTHP is a large set of interviews conducted with individuals who had knowledge of local history. Each interview was recorded, transcribed, and then edited lightly to preserve the language and speech patterns of those interviewed. All oral history interviews have been printed on acid-free paper and bound and archived in Nye County libraries, Special Collections in the James R. Dickinson Library at the University of Nevada, Is Vegas, and at other archival sites located throughout Nevada. The interviews vary in length and detail, but together they form a never-before-available composite picture of each community's life and development. The collection of interviews for each community can be compared to a bouquet: Each flower in the bouquet is unique—some are large, others are small--yet each adds to the total image. In sum, the interviews provide a composite view of community and county history, revealing the flaw of life and events for a part of Nevada that has heretofore been largely neglected by historians.

Collection of the oral histories has been accompanied by the assembling of a set of photographs depicting each community's history. These pictures have been obtained from participants in the oral history interviews and other present and past Nye County residents. In all, more than 1,000 photos have been collected and carefully identified. Complete sets of the photographs have been archived along with the oral histories.

On the basis of the oral interviews as well as existing written sources, histories have been prepared for the major communities in Nye County. These histories also have been archived.

The town history project is one component of a Nye County program to determine the socioeconomic impacts of a federal proposal to build and operate a nuclear waste repository in southcentral Nye County. The repository, which would be located inside a mountain (Yucca Mountain), would be the nation's first, and possibly only, permanent disposal site for high-level radioactive waste. The Nye County Board of County Commissioners initiated the NCTHP in 1987 in order to collect information on the origin, history, traditions, and quality of life of Nye County communities that may be impacted by a repository. If the repository is constructed, it will remain a source of interest for hundreds, possibly thousands, of years to come, and future generations will likely want to know more about the people who once resided near the site. In the event that government policy changes and a high-level nuclear waste repository is not constructed in Nye County, material compiled by the NCTHP will remain for the use and enjoyment of all.

—R.D.M.

CHAPTER ONE

RM: Homer, could we start by you telling me your name as it reads on your birth certificate?

HH: Homer Hooper. I was born November the 14th, 1924, in Owyhee, Nevada.

RM: What was your mother's name?

HH: Alice Kawich.

RM: Is that right. Was she related to Chief Kawich?

HH: The granddaughter.

RM: And what was your father's name?

HH: Art Hooper.

RM: Where was your mother from?

HH: She was born in Goldfield.

RM: And her grandfather was Chief Kawich?

HH: That's right.

RM: How many children did Kawich have?

HH: I don't know.

RM: What area was your father from?

HH: Monitor Valley.

RM: Were they both Shoshone?

HH: That's right.

RM: And where did you grow up?

HH: Well, mostly-here in Reese River - right in this area.

RM: Were you living on ranches then?

HH: Yes.

RM: Were the ranches owned by Indians, or whites?

HH: Well, back in the '30s - along in '36 when we first moved into the country here - the people still on the ranches who owned them were whites. They eventually sold their cattle and so forth and moved out.

RM: Where did you live before you moved here?

HH: I was going to school in Schurz, Nevada.

RM: Did your family live there, or were you just going to school there?

HH: No, we moved there.

RM: I used to live at Reveille, on the east side of the Kawich range, and I've always been interested in Chief Kawich. Is there anything that you could tell me about him?

HH: I don't know how to describe him. My folks told me that the Kawich Mountains over there were named after him. There's a statue of him down there somewhere. They said he was a pretty good chief and everything.

RM: Did he live right in that area, or did he kind of roam around? HH: He probably roamed part of California, Utah and Nevada. They moved back and forth, from what I understood.

RM: Where did your mother grow up?

HH: Tonopah.

NH: She went to school at the Indian school in Riverside [California]. RM: Did Chief Kawich live there in Tonopah, too?

HH: Yes. I suppose in the boom days . . . well, they were there before the boom days, I suppose, and then Jim Butler moved in there. I don't know too much about it, but that's what they told me. They told him that a person had to marry into the family before they could expose the gold or silver that they found, but he saw the valuable minerals that the people were using when he first moved in there. He wanted to know where it came from. That's how that came about - where he had to marry into the family.

RM: You mean, Kawich told him that he had to marry in before they'd tell him where it was?

HH: That's right.

RM: And he did marry in - he had an Indian wife, didn't he?

HH: That's how they showed him where it was.

RM: Do you know what Jim Butler's wife's name was?

HH: No, I don't recall, off-hand.

RM: And they had a couple of children - I've heard one, and I've heard two, children.

HH: Two - yes.

RM: Whatever happened to those children?

HH: [chuckles] It seems like the people didn't talk too much about that. Or when I was a kid I just overlooked things or whatever it was. It's been a long time. The people [involved have] passed away; you should've been around earlier [to ask them].

RM: Yes, really.

HH: When my folks were still around - Grandma and all - they knew all that.

RM: When you were growing up, did your family practice much of the traditional Indian culture?

HH: Well, they sang and they'd wear leather clothes and such - tan their own hides and so on. My mother and grandma did beadwork and made baskets and all sorts of stuff.

RM: Did they collect any of the wild foods that the Indians lived on before the whites came?

HH: Yes, berries and pine nuts and such.

NH: Wild onions, wild carrots . . .

RM: Do you know any of the places around here where the Indians used to gather?

HH: There's not much vegetation anymore. I suppose chokecherries and elderberries and all sorts of stuff would still be in the canyons.

NH: Isn't Big Creek one of them? They used to have a big Indian camp there.

HH: Oh, yes - Big Creek.

RM: There were a number of Indian camps in Reese River Valley and up the canyons, weren't there?

HH: Yes - in different spots.

RM: Do you know any of the spots where they used to camp?

HH: Well, I guess the biggest camp was there at the mouth of the canyon of Big Creek. My folks used to say that on the weekends, they'd all single file into Austin, and when the train come by, they used to watch a train on the railroad.

RM: What do you mean, "single file"?

HH: They walked single file. They had a regular trail there that they'd follow in.

RM: What other canyons were their camps in?

HH: Boy - I don't remember very well anymore. [chuckles] I suppose wherever there was vegetation and so on. Some of the main canyons with running water and stuff . . . but they'd move about, hunting pine nuts and things. And then later in the fall, they'd move out of there, down to a lower valley or wherever they'd find shelter.

RM: Where were the good pine nut hunting areas? Were there any special ones that you recall?

HH: Well, in those days there was more vegetation, and pine nuts grew just about every year - wherever there are pine trees in Nevada. But anymore it's in spots, just like the rain. Sometimes the rain is cut off, just like it was on a faucet - just like this down here.

RM: Yes - like a line.

HH: It will wet the lower end and be dry on the upper end, and so on.

RM: There was more moisture in the old days?

HH: More moisture; yes. When we first moved into this country it rained and rained for weeks - 2 weeks at a time - and it was always miserable; wet. And grass - you name it - there was a lot of hunting and a lot of vegetation then. But through the years it's changed quite a bit - it's dried up here and there in certain areas.

RM: How long did you live at Schurz with your family?

HH: I don't recall right off-hand. Probably 5 or 6 years, somewhere in there.

RM: Where did you live before you went to Schurz?

HH: Owyhee.

RM: Why was your family up there?

HH: Oh, they traveled from here to there, wherever there was work.

RM: What kind of work were they doing?

HH: Just ranch work - cowboying. My dad was a cowboy and he'd ride during roundups and help hay during the summertime. He it up a lot of hay and stuff for different ranchers.

RM: Was he a pretty good horseman?

HH: Oh, yes.

NH: He was well-known for the horses that he broke.

RM: Is that right? Where did he learn his horsemanship?

HH: Home, I guess. They had a big ranch where he was born, there in Monitor Valley. His people had a lot of cattle and all that, so [he learned] from his fathers and grandfathers and so on, I imagine . . . they ran horses all their lives.

RM: What ranch was it that he worked on there?

HH: The Potts ranch.

RM: Did he work there a long time?

HH: Yes. The Hooper family were all born there. I don't know about the dad or anything, but .

RM: How many brothers and sisters did your father have?

HH: Four, I imagine.

NH: Emily was one sister; who were the other sisters?

HH: I don't know; it seems there was another one they talked about; I really don't know. I don't know who would know.

RM: But it was a fairly large family?

HH: Oh, yes.

NH: His family has 13 kids.

RM: Could you name your brothers and sisters?

NH: Gene . . . he's dead now. And Homer, Levi, Owen, Vernon, Orpha……

HH: Orpha's the oldest.

NH: and Verna, Ophelia . . .

HH: Lucille.

NH: Laura, Darlene, Ernie and Hubert. And I don't know the names of the ones who died when they were small. Alla Mae is one.

RM: All of the ones you named lived?

NH: Yes, they all lived. Two of them are dead now, but they grew up to be adults.

RM: And you're the second oldest?

NH: Yes, Homer's second oldest.

HH: Out of the girls, Orpha's the oldest; she's the oldest one of Art and Alice Hooper's children

NH: She's in Fallon - Orpha George.

HH: She might know things; she stayed home a lot with the family and she and my mother talked about . . .

NH: He went away to school when he was 5 - he went to school in Stewart.

RM: That was really young.

NH: Yes, they took them as babies, then.

RM: Do you remember anything about Stewart?

HH: [chuckles] Oh, a little bit, I guess.

RM: Why don't you talk about what it was like?

HH: Well, my brother Gene and I, and Orpha, the oldest one, went to school in Stewart. I forgot what year it was - about 1929. It was a pretty good educational school. It's a boarding school. We were in the small boys' cottage at first, and the girls had their own cottage - small girls'. And different groups had different cottages, like bigger boys and the bigger . . . to a certain age, that is. But anyway, I went through a lot [chuckles] over there.

RM: Were you lonesome?

HH: Yes, but they'd keep us pretty busy. We'd always keep busy doing something. They had different jobs for each individual - clean up the yards and scrub the floors and clean the wind s, all housework and things like that.

NH: How did they decide who went to the school? Did they make everybody go there? (Homer always says about everybody we talk to that's his age, "I went to school with him; we all went to school at . . . ") Did they just come through here and pick you guys up and take you to school? HH: Yes. Because during the Depression it was hard to live, with so many kids and so on. So people from Owyhee - the kids my age and some of them even younger - went over to Stewart school. A bus picked the whole bunch up and took us in there. When we were able to get around better, then our folks wanted us back, so, we came back. We lived in Schurz, then - wherever my dad found a job. He helped build, Webber Dam up there, and that was one of the biggest jobs at that time for the Indian people. Building it lasted several years.

After we left there, we came over here and whoever wanted to go to school in Stewart . . . and you could select any job you wanted - you name it, they had jobs of all descriptions, from cooks, laundry, arts and crafts, bakery, paint shop, auto mechanics, welding . . . gosh, everything you could name. That's how they trained you for jobs after you grew up. You got an education - you'd work part time and then go to school part time.

RM: What job did you take?

HH: Well, I've been through several of them. I worked in the laundry and I was in the paint shop for a while. They put you on [a job for] any length of time you wanted. If you didn't like it, you could choose another trade. Some I like and some people [chuckles] I don't pay attention to. The idea [was to find] whatever suited you best. I took up a little bit in mechanics and welding, too - a little bit of this and that.

NH: Did you learn to do silver work there, too?

HH: No. Arts and crafts was where they carved wood and stuff and made picture frames or any animal form or things like that; they made them out of mahogany.

RM: So you came to Reese River when you were about 12?

HH: In '36, yes.

RM: Did you go to school from here, or anything?

HH: Yes. Bowler Ranch down there had a school. Then they wanted me to go to Stewart, so I went back to Stewart again. And that's when I took up all these different things that would help me out through the later Years.

RM: How long were you at Stewart the second time?

HH: Gosh, I can't recall that, but it was a while. I took up poultry -raising chickens - and fanning, like planting vegetables and working in the dairy, milking cows, and on the Tube Ranch, where you fed the cows. A different bunch fed the cows in the morning very early, about 4:00. Then the kids wbo milked the cows came in later. And they had a butcher shop; I worked in the butcher shop for a while. And then they had Jack's Valley Ranch, where they raised the cattle and so on for the school. was up there for a while - I was just back and forth, looking for different trades. They had everything in the line of raising stock: pigs, cows . . . they raised everything for their own use.

NH: They were what you call self-sufficient - they'd raise all their own food, their own meat, everything, and the kids all had to do the work to run the place. That way, they didn't have to it money out to buy things and the kids got to learn the trades while they were working.

HH: That was really a good school.

RM: Did you like it there?

HH: I liked it there pretty well, because of the training and stuff.

RM: Did you speak Shoshone in your home when you were growing up?

HH: Oh, yes.

RM: They didn't let you speak Shoshone at school, did they?

HH: No. Every school I went to would punish you for [chuckles] saying even one word of . . .

NH: He didn't speak English when he went away to school, did you?

HH: Not very well.

RM: So you had to learn English when you went there the first time?

HH: Yes. It was pretty tough there.

RM: Do you look back on it with any bitterness?

HH: About not speaking my own language?

RM: Yes.

HH: Yes, that part is . . . I don't know why they did that. But now they want people to go to school to learn the Indian language and . . . I wonder why that is?

RM: I don't know.

HH: Maybe they wouldn't learn English real well, because . . . I was mixed up pretty well when I started in - it sure takes a long time to [chuckles] get on to it. But I still speak my own language.

RM: You still speak Shoshone?

HH: Oh, yes.

RM: Do you speak it well, would you say?

HH: I would say so.

NH: He has a hard time finding people who still speak the language, to have someone to talk to and practice with, because none of the young people speak it.

RM: Are there many people in the valley who speak it now?

HH: Not very many.

NH: Not hardly any, now - maybe 5 or 6?

RM: Is that all?

HH: Yes.

NH: Maybe 10.

RM: The woman who's going to type this up studies Indian languages. She lives in Colorado, but she just finished writing a grammar of Comanche, and Comanche is very close to Shoshone. Why don't you say some things in Shoshone for her? Give her a little taste of it. [chuckles]

NH: Don't be bashful.

RM: Say "It is a very nice day in Reese River."

HH: Tsaan^ndabe Reese Riverdat^.

[Transcriber's note: Shoshone has certain sounds that English lacks. use ^ to stand for a high mid vowel, somewhat like the e in English the. I use to stand for the voiced velar fricative, which is like the Spanish when it occurs between vowels, as in lago, 'lake'. Mr. Hooper seldom repeated his utterances, so these transcriptions are generally based on a single hearing of tape recorded speech.]

RM: Why don't I talk to you in English, and you talk to me back in Shoshone? Do you want to try that?

HH: Every word's backwards from English in the Shoshone language.

RM: How do you mean?

NH: Like Spanish is to English.

HH: Yes. We say the word first, and then [the adjective]. I used to try to translate some of it, but it's kind of tough, sometimes.

RM: OK. I'll just ask you some questions. What is this, Homer?

HH: Aik^nbuph.

RM: That's black - holding a can of black pepper. What's this?

HH: Some things the Indians never had a word for. We just say "peanut butter" [for that].

RM: What's this? (I'm pointing to my jacket.)

HH: Goot.

RM: Have you ever been on top of Arc Dome?

HH: TsoondA (that means "quite a bit").

RM: "Quite a bit?" How did you get up there?

HH: Punguwa nendowe asakorxi"wa ningwoiowan. "Riding a horse way on top of there."

RM: Riding a horse? How long did it take you?

HH: Natgwidanb^ unde. "Half a day."

RM: Where did you start from?

HH: Kahnigahn^n - that means, "from the house."

RM: From the house?

HH: Here in the valley - yes.

RM: Could you ride the horse all the way?

HH: Oh, yes.

RM: Was there snow?

HH: Uwa nandekath^n. That means, "A little bit of snow."

RM: "A little bit of snow." It sounds neat, doesn't it?

NH: I like to listen to him talk in Shoshone.

RM: Homer, one of the things I'm sort of interested in doing is learning the Indian names for the places around here before the whites came. I'd like to make a map of Nye County that would be, not a white man's map, but an Indian's map, with the Indian names. Can you think of some things in the area here that would have an Indian name? Or, maybe other areas of Nevada, that you've been to, particularly Nye County, that have Indian names rather than the white name.

HH: Well, the mountains over there - toyabe. [Stress is on the first syllable.]

RM: Toiyabe? [Stress is on the second syllable.] That's an Indian word?

HH: Well, that's how it's [written] on the map - I guess that's the way it's spelled, too.

RM: What does toyabe mean?

HH: "Mountain "

RM: What do you call the Shoshone Mountains?

HH: Nnten doyabe. That means, "Indian Mountain."

RM: Oh - "Indian Mountain." What did you call the Toquima Mountains?

HH: Where are those?

RM: The Toquima are the ones on the other side of Smoky Valley - that border Monitor Valley.

HH: Monitor Valley?

RM: Yes - the Mount Jefferson mountains

HH: Oh - Mount Jefferson.

RM: Did they have an Indian name?

HH: No, I don't think so. They may have had different names for the different canyons. Like, down here - they call it Yomba Honopi..

RM: And that is . . .

HH: "Carrots Canyon," or "Carrot Creek." It's Marysville Canyon down here.

RM: Did Stewart Canyon have a name?

HH: No. I don't recall one, at least. Nobody's ever called it by an

Indian name - Stewart Creek is all I know of.

NH: And yomba - this is the Yomba Reservation.

HH: Yes, "Carrots" Reservation.

RM: Yomba means "carrots"?

HH: Yes. And then there's Carrot Canyon over there - Marysville Canyon.

RM: There were a lot of wild carrots there?

HH: Yes. They grow along the creek, there.

RM: Do they grow in other places around here?

HH: I suppose wherever there's a little bit of water - that's where you find them.

NH: We used to dig wild carrots on the summit of Union Canyon.

RM: Is that right? What do they taste like?

NH: Carrots.

RM Are they

NH: Yes.

RM: They are what we would call a carrot?

NH: But they're skinnier. They're smaller around and they look more like a root. They're a yellow color - the carrot color?

HH: Sort of; yes.

NH: Not as yellow as ours; a lighter color.

RM: But they are a carrot - do you eat the tops, too?

HH: No. It has a stalk about like that, with white flowers, and the leaves are similar to the regular carrot leaves. But there are very few - it's not branched out like carrots are.

NH: And then they have quite a few wild onions here, too.

RM: What is the name for the wild onion in Shoshone?

HH: Muha.

RM: Do they grow where the carrots grow?

HH: In places where there's moisture and such. For instance, up through the canyons here - Clear Creek and Stewart Creek. You find them under the high sagebrush or cottonwood trees and places like that.

RM: Well, your family came here when they first started the reservation; is that right?

HH: Yes.

RM: Tell me about how you heard about the reservation that they were going to start here and how you happened to come over here.

HH: Well, my mother and my folks talked about it, and then they wrote to the governor and so on, trying to get a reservation started here. But they chose this place.

NH: His mother was the one who started it.

RM: Your mother started it! Wow! How did she do that?

HH: Well, the people got together - the grandpas and uncles and so on - and they wanted to know if they could find a place to settle, I guess. They selected this valley here because the people knew it pretty well, and some of their relations were already in the valley, working for different ranches. And I guess that's how it all come about. They were saying, "Why couldn't we have a reservation, when the Paiute people over there's got a reservation?" And [they were talking about] how to go about it. So they write to, as I said, the governor, and different things. I guess they looked into the country here to see if the ranchers would sell out, and they did And that's how they come to get in here, in this valley.

RM: How did they get the government to go along with it?

HH: I suppose that's where the governor, or whoever . . . My mother's letters were up there. I could tell you better, but I don't know, where they are; they used to be up at the big house - the Bell Ranch.

RM: Her letters were there?

HH: Yes - where she wrote, and who she wrote to . . . who had more pull to look into the situation.

RM: How long did she work on it before she came over here?

HH: It must've been several years, I would say - 3 or 4 years or something.

RM: Yes. The government doesn't move easily, do they?

HH: No. Then they finally got in here. When we first moved in, we were down at Bowler Ranch, and the people who owned the ranches were still in the houses. My dad and the others worked for them after we moved in there. We moved into tents down there.

RM Is that right? Where is the Bowler Ranch located?

NH: You came past it when you can up from O'Tooles'.

HH: It's the first ranch below O'Tooles'. It has a brick house and stuff and the barns are in there.

RM: Oh, and the road kind of goes right through the ranch?

NH: No - that's too far down.

HH: That's the Whooley Ranch. O'TOoles used to have it, too. No, it's just between O'Tooles' and the Whooley Ranch. Just a couple of miles north from Bartley O'Toole's place is the Bowler Ranch.

RM: Who owned it, at that time?

HH: The people there were named Bowler - John Bowler.

RM: And they owned it at the time your family came over here?

HH: Yes.

RM: And you lived in a tent there?

HH: Yes. I guess the reason we had to live in tents is, when they said they would sell out, we moved in right away, instead of waiting until they had a chance to move their cattle out. They had range back on the other side of the mountain over there - Ione and . . . so they had their cattle scattered out and it took them a while to gather them all up, and there were different things they had to do before they moved out.

This place was the Derringer Ranch. It belonged to John and George Derringer - they were still there. They owned ranches and a lot of cattle. So the Indians moved in here. But there were other Indians already living here who worked for different ranchers, and they had old willow and mud dwellings they'd built to live in. When they moved out, some of the people moved into the houses there that the people had owned.

I think it was a year later that the government started building those cinder block houses. They built down at Bowlers' first, and then up at the Bell Ranch. They didn't build any down here at Derringers'. There was a Bell Ranch up above, right . . . They made their own cinder blocks. We helped, when we were kids, pour the cement in those trays and let it set a while and dump it out and build those cinder blocks for houses.

NH: Tell him how you used to travel from here to Fallon and so forth.

HH: We had an old pickup and we traveled to town once in a great while. (We hardly moved, you know.) When we first moved in here these old roads were just a wagon trail. You'd very seldom see a car in here up the valley - once a month, maybe. [chuckles] Not even that, sometimes. I think the stage was the only one that came by at a certain time. Brush was growing in the center of the road, and where the cars had gone over, it was cut like a hedge.

RM: [chuckles] I'll be darned.

HH: [chuckles] Just two tracks, that's all there was. People were still traveling on horseback. People looking for work came in with pack horses and stuff.

RM: Indians, or white men?

HH: White people looking for jobs. They worked for a while and away they'd go, after the job was done - haying or riding for the ranchers -buckarooing.

NH: Who was the guy who used to come by here on the wagon? You used to catch a ride on the wagon to Ione.

HH: Well, most of the people had buggies and wagons - they still traveled that way, then. Of course, it was a long way from gas and everything. There wasn't much money around then anyway, and I think people . . . the men worked at the hay fields for 25 cents or 50 cents a day - 75 cents a day. It finally went up, in the later years, to $1 a day. So there wasn't much traveling there - just a few cars. People didn't go into town to buy gas like we do now. We go to Reno in a few minutes now, it seems like anymore. It used to be [chuckles], Fallon was such a distance that you had to sleep a couple of days [on the trip].

NH: Yes, that's what I was wanting him to tell you. They used to travel with the wagon and all to Fallon, and they'd camp along the way 2 or 3 days till they could get to Fallon.

HH: Even with a car. Some had cars, and when it got late, the old people had their bedding with them and would can out right there, along the road. They'd get groceries one day and then start back. When it got dark, why, that's where they stayed.

RM: They didn't drive at night?

HH: No.

RM: Did they have lights on their cars?

HH: Some did, but people who were working all the time got tired, and when the sun was going down that was the time to settle down. That's the way they were, mostly - not like now, with people staying up till 2:00, 3:00 every night with just a few hours to sleep and get up to go to work or something. In those days, they'd go to bed with the chickens - when the sun went down. They didn't have television, or various things they have now.

RM: Yes. And they'd get up, when the sun came up, wouldn't they?

NH: Oh, yes - before. Some of them got up about 4:00, 5:00. . .

RM: Is that right. So they could be out working when the sun came up?

NH: Oh, they were already doing the chores. Then when they were ready to go out in the field, they got the horses all fed and harnessed and ready to go by sunup.

RM: Could you tell me who were the first Indian families that came into the valley when they decided to make it a reservation?

HH: We were - the Hooper family and . . . I think it was Darroughs.

RM: Were they from Darrough Hot Springs?

HH: Well, it was a distant relative. And there was Dimmie Jackson.

NH: What about Willie Bill? Was he one of the first ones?

HH: No, they lived in the valley down there - working for the outfit down at the Hess place.

RM: Is that about all the families that came in at first?

HH: No, there was . . . gosh, I don't remember too well.

NH: How about Wickson Charlie? Did he come in later? Or the Birchims?

HH: Yes. All those people came in later.

RM: Did they all come from Schurz?

NH: Most of them, I think.

RM: So they were Shoshones living over there on the Paiute reservation?

HH: Yes.

RM: How did they decide which family went where? How was it you went to the Bowler place, and not some other place?

HH: Well, it was their choice. Whoever wanted this place or that place had already looked it over and decided where they wanted to stay.

RM: What if 2 families wanted the same place?

NH: They'd pull a straw, I suppose. But, then, there weren't too many families at that time, to crowd each other. If they'd say, 'Well, you have this one or that one," then that's what they took. It was new to them, and they were in a hurry to settle down. That's why they weren't particular about where they were going to settle; they just wanted a place.

RM: About how many families came in during that first period?

HH: Goodness. My brother Levi has the book on all that.

NH: The 1930 census?

HH: Sure, they have a book down at the tribal office.

NH: He's got the census all the way from 1930, doesn't he?

HH: Yes. My brother Levi is the tribal chairman. He lives right up here. And that book has the years that the people have been here, and the names, all written down with those by-laws and so on.

RM: Did many other families come after the first ones?

HH: The later ones, yes. I don't remember very well. As I say, I've been to school, and then I was able to work on different ranches, and then I started working in the mines and different places, operating equipment and all that sort of thing.

NH: And during the war, he worked at the ammunition depot at Hawthorne.

RM: Oh. Well, where did they come from? Were the Indians who came here mostly coming from Schurz, or did they start coming from other places, too?

HH: Other places. Some of the people had actually lived here in this valley. As I said, there were willow and mud houses that they built that they lived in for many years. And down at Pat Welch's, they had a lot of Indians working for that big company.

RM: Do you mean a big cattle company?

HH: Yes - the ranch down this side of Austin. They used to have a lot of cattle and stuff and [a lot of work during] the haying and whatever; they had big ranches.

NH: They had a regular Indian camp at the Welch Ranch.

RM: About how many people would you say, were living there?

HH: I couldn't say, right offhand, how many families were there, but there were quite a few of them. The people from there wanted to come into the reservation, so the tribe voted them in and so on; that's how they came. And there were some from Austin, from Duckwater, I think

Smoky Valley . . .

RM: What was the rule as to who could came in?

NH: You had to be half-Shoshone; you still do.

RM: How much land did they give each person that came in?

NH: Different assignments have got different acreage.

HH: Yes, because of the size of the ranches. This ranch is a certain size, and the other ranches are different sizes. So they had to divide them . . .

RM: They gave each family a ranch?

NH: Well, they broke up the regular ranches - they'd break them up into smaller sections and then the families made their own ranch from the smaller sections.

RM: I see. So some of the ranches got broken up into smaller units.

NH: Yes.

NH: How many different places are there on the Bell Ranch?

HH There used to be 6.

NH: Six different places out of the one ranch.

HH: Even 7. There was one - the Darroughs lived farther up . . . 7 on that ranch.

NH: One of the governors or something [in Nevada] used to live on the Bell Ranch. He was buried in the cemetery - he's got a big headstone up here in the white section, you might say. They had different sections, as they do everywhere.

RM: In the graveyard, you mean? So they've got an Indian section and a white section?

NH: Austin has the same thing.

RM: Did each family, then, go into the ranching business once they got here?

HH: Yes. What they used to do when they came in was to select a certain amount of repayment cows for them and give them a certain length of years to pay up the full amount of cows that they were issued. That's how they'd get started. Of course, there was a lot of water and so on then, so everybody had hay. EVerybody cut hay, and then they helped each other. They'd start from one end of the valley; they'd put their work horses and mowing machines and rakes and things together and they'd came right down through the valley and finish off. That was a pretty good deal, because there was a lot of help putting up hay.

RM: How long did it take to go from one end of the valley to the other?

HH: Probably 2 months - somewhere in there - to put up the hay for all the reservation.

RM: That's just cutting the wild hay, right?

HH: Well, they had alfalfa patches - I think each ranch had an alfalfa patch at that time.

RM: This was Indians, right, doing this? Most of the whites moved out, didn't they?

HH: Oh, they almost all did; yes. They sold out and moved out.

RM: Who stayed? The O'Tooles stayed, didn't they?

HH: Yes - they didn't want to sell.

NH: You'll notice the reservation goes down to O'Tooles', then jumps O'Tooles' and then there are 3 more places down below there before you come to the end.

RM: So it became an Indian community, really, whereas formerly it had been a white community with Indians.

HH: Yes.

RM: Why do you think the ranchers sold out? Was it because they were going broke?

HH: I suppose some were, yes.

RM: Because of the Depression, plus, I understand, when the Taylor Grazing Act came in the Forest Service had cut back on their allotments and everything. So they were probably having a tough time, weren't they? HH: Oh, some of them, yes. They had cattle, but you know how that goes - in those days you couldn't give them away. But I think they held off till the price of cows come up. They must've stayed a year or two before they sold completely out. I think that's why we had to stay in tents [chuckles], waiting for them to get out.

RM: How long did you have to stay in a tent?

HH: Goodness - a couple of years, I suppose.

NH: And in this country, that gets mighty cold in the wintertime.

HH: Oh, boy.

RM: That must've been terrible. How did you stand it?

HH: Well, we had 10-by-16 ridgepole tents - put a wall up, and it would be just like a house. But you've got to stretch the canvas real tight so when it snows it won't sag down and tear it up. During the night, if it's snowing heavily, you usually knock it off, and then the stove would dry it pretty fast - we had a cooking stove in there. The tent was airtight.

RM: Did it ever leak?

HH: If you'd touch it, it would. The kids were pretty well aware of it, because the mothers got after them. They were pretty strict.

RM: So if you touched it, it would start dripping?

HH: Yes. If you reached your hand over there, it would start dripping through. But as long as you didn't touch it, it was waterproof. The canvas will tighten up like that and it won't leak.

RM: Did you put waterproofing on the tent?

HH: They did have waterproofing, but it was hard to put on, at the time. Now you've got sprays - you can just spray them on there. But nobody uses a tent anymore. [chuckles]

RM: Right - now that they're [easily] waterproofed. [laughter]

NH: Now you can get them out of nylon. [laughs]

HH: You bet - they make it out of different things were it's really waterproof, isn't it? Boy, in those days it was tough going, all right. I used to chop wood for Bowlers down there - fill up a big old wood box ¬and I would get about 10 cents. And they had a dog that used to bite me on the heel every time I went over. I had to knock on the door to get the axe out of the house, and [chuckles] as soon as Bowler's wife opened that door, that dog would jump out and nab you right . . . and it'd sting too - and draw blood, sometimes.

RM: Ohl

HH: What could I say?

RM: Yes, really. You couldn't kick it, could you? You'd lose your job. [laughter]

NH: How about Carl Worthington - was he here then?

HH: Yes, he had the ranch up here at Clear Creek.

NH: He stayed here after all the Indians came in, didn't he? Did he sell out then?

HH: Yes, he hadn't sold out yet. He was still living up there for a while.

NH: And that was the first place you went to work. Was that the first place, or was O'Tooles' the first place you went to work?

HH: O'Tooles'.

RM: You went to work for Bart O'Toole's father? That was the first ranch you worked for?

HH: I believe so.

RM: What did you do there?

HH: Ran a hay rig.

NH: And handled all the nasty horses. [chuckles]

RM: He had nasty horses?

NH: Oh, boy. He had some of the meanest horses you ever saw!

RM: Is that right? What would they do?

NH: Oh, those horses . . . you'd catch them in the corral. You'd have to rope them and put them in a tight stall with a snubbing post to put a halter on them. The walls were about 4 feet high and about that thick. The horse would have just a back showing. You'd put a harness and everything on right there. They would kick your head off if you got behind them or touched them or anything - if you'd make a noise, they'd start kicking. And they'd strike, too.

RM: With their front feet?

HH: Oh, yes. So you'd have to snub it close to put a halter on them. You'd try to get the halter on and they'd jerk their head like that, and you had to watch them so they wouldn't hit you on the face. Boy, they were wicked. They'd jump up and strike; some of them would bite. You had to watch them. You'd put the halter and bridle on, then put the harness on, in the stalls, and lead them out.

RM: What were they like when you got them out? Would they behave?

HH: [chuckles] They were a little better with the bit in the mouth. But at any noise . . . if you were leading them, they'd run away from you. Those big horses - of course, I was small, but they were big, actually. You had to hold them real tight and step to one side, because they'd run over you.

When anything made noise, they'd take off. When you'd put the horse on a piece of machinery - whatever you were using . . . I used to take a long, stiff wire like that and I'd lie close to the ground and reach over there and bring the chain, and hook it on the . . .

RM: Oh. So they couldn't get you?

HH: That's right. Boy, as soon as it touched their leg here, they'd start kicking me. They'd kick right over me like that all the time. [chuckles]

RM: Ohl Just getting them harnessed was dangerous, then?

HH: Oh, you bet. But they knew I could handle it, so they gave me all the worst ones that they had.

RM: Why were his horses so bad?

HH: They were spoiled from other people who couldn't handle horses ¬other people who let them get away with certain things, and pretty soon they'd bluff the people, and . . .

RM: Oh. What should you do when they do something? Whip them, or what? HH: It won't do any good to whip them.

RM: Well, how do you make a horse like that behave?

HH: Work them hard. [laughs] Tire them out. Then they get gentle for a while. But next morning it'll be the same thing.

RM: Isn't there anyway you can reform them - make them gentle?

HH: I'm talking about older horses that have been through it already. But a younger one - if somebody had spoiled it, it wouldn't take long to break him out of it. Tie up all the feet together so they won't move and crawl around them and pet them around and don't abuse them. Just pet then around and make them know that you don't mean any harm. Then they get gentle and like a pet. It'll be a one-man horse if you break it and don't have anybody else around; but if you have people around the horses that you're breaking, then they get used to other people, too. But if there are no other people around and you handle it by yourself all the time, it'll be a one-man horse - yours. Then when somebody else come about, they act up again.

RM Didn't they know how to handle horses at the O'Tooles'?

HH: [chuckles] I guess it's the way the workers handled those horses. Different people would come in there who couldn't handle horses right. If they let them get away with it once, that's it. Then they're hard to handle.

RM: Well, what should you do when they try to get away with something? HH: Well, as I say, get ahold of them and show then that you're not going to harm them. Tie up all the legs where they won't kick at you and stuff. If you don't, they keep kicking at you all the time and they never quit. But when they try to kick, if you've got all 4 tied together, they'll fall down, and they're afraid to fall down. They're afraid to lie there. So you let them back up and tie them back up again. Pretty soon they'll standstill, and you can pet them around, all the way around. And crawl under their belly and all that sort of thing.

NH: Homer [and another guy] used to have 2 deer camps up here, too.

RM: What did that involve?

HH: Well, it made a little bit of money during hunting season. You had to get a permit from the Forest Service to build a corral for the horses, to rent horses out to deer hunters. It wasn't much, but it was a lot of fun renting horses out to deer hunters You find all kinds of people there, too. It would scare you half to death, because the horses weren't used to too many people being around then. They were shy, and they were liable to kick at you and things like that. Some of them would buck . . . the way some of the people go about it, when they approach a horse the horse will feel it, and then start a-bucking.

RM: The horse knows they're a greenhorn, or what?

HH: Yes, you might say greenhorn, all right. [chuckles]

RM: A horse knows those things, doesn't it?

HH: Oh, you bet - just like a dog. Dogs will bite certain people. Horses shy from other people, just like dogs will.

RM: They do it with people when they know they can get away with it? Is that it?

NH: Well, some people that are mean. Tell him about when you got kicked in the face with a mule.

RM: You got kicked in the face?

HH: Oh, yes.

NH: Right between the eyes.

HH: A mule - my work mule . . . well, we worked him in the field and so on, but we used him as a pack mule. I unloaded a deer off him one morning, and the people had taken off, after I loaded it on the pickup, and the old mule was standing there. I walked up to him, got ahold of the halter rope and the cinch was hanging down, that I had the deer tied with. I reached down there. like that, and that's all it wrote. That mule spun around and whacked me right here on the forehead. The impact stunned me, but I was close - it didn't knock me down; just staggered me back. And I could feel a bump. I went like that and my hand stuck out like this . .

RM: Ohl Your hand stuck out an inch or two.

HH: Yes, like a goose egg - it went like that.

RM: What did you do to the mule?

HH: Nothing. There isn't much you could do. You can't punish them; they wouldn't understand. Just like those horses. They're playful - they start kicking and they're liable to kick you, just playing. But that's the way they are. You can't make them understand.

RM What did you charge a day for renting a horse at your deer camp?

HH: Five dollars a day.

RM When was that?

HH: Back in the '40s.

RM: Where did you get the horses?

HH: Well, we raised our own horses. I started out with Worthington's - he had a bunch of horses up here. We put our horses together, and I was with him, at first. He had the permit and everything.

RM: Did you make some pretty good money at that?

HH: Oh, yes. It was slow, but in those days, $5 was a lot of money. Everything was starting out [after the Depression]. There were a lot of jobs, too, but they didn't pay very much.

RM: What did a job pay then - on a ranch?

HH: I'd say maybe $1 a day, $1-and-a-half a day.

RM: And that wasn't an 8-hour day, was it? I mean, that was sunup to sundown.

HH: You bet.

RM: What were some of the things that you did, when you were working on a ranch.

HH: Well, the ranchers had milk cows and chickens and calves that had to be fed in different corrals. You'd feed them early in the morning - at daybreak - and then if you had to go out in the field you'd water and harness your horses and feed them and they'd be ready to go after you'd go and eat breakfast. Then you'd get out in the field and be out there all day, according to what you were doing - you were either mowing hay with the horses, or using the rake to rake up the hay. Then you'd bunch the hay - the alfalfa hay - and pitch it by hand, on a wagon. They had nets on the wagon. You'd fill the whole wagon up, one on each side of the wagon and one on top of the wagon, and they had these Mormon derricks with a cable on it. They'd run the wagon under there and hook the net together like this - it had a ring on the end of it - and hoist the whole wagon load at one time and put it on a stack. (There were 2 on a stack.) They'd stack it and make the edge smooth like this on the corners - build it right on up. That's a job, pitching hay.

RM: Dusty and dirty and . . .

HH: You bet. The stacker's the one. His face will be black at night from the hay dust and stuff.

RM: Ohl

HH: When they smiled I used to laugh at them - the teeth were all black from breathing through their mouth. Just think what it does to their lungs.

RM: Yes.

RM: What other ranchers did you work for in the valley?

HH: I worked down at the Hess place for the Welches.

RM: The Welches had the Hess Ranch?

HH: Yes. Then they had their home ranch, too, down at this end - on Highway 50. I worked for them different times, and at Carter Ranch. The Welches had that, too. Then the next one is O'Tooles'. Above the Welches' ranch is the Billy O'Toole ranch. I worked for them. Then the Bart O'Tooles had the Schmalling Ranch up here - I worked for that outfit. Then I worked for the Worthingtons - put up their hay.

RM: Where were they?

HH: Clear Creek - right up this way. Then I worked for Derringers, putting hay up, before they left. Then stayed here a couple of years at the most, I think.

RM: And then you said you did some mining?

HH: Yes.

RM: When did you do that?

HH: In between times, when there wasn't much to do. When people gathered their cows and things, I'd go mining in places like Grantsville.

RM: This was in the '40s?

HH: Yes, some time in the '40s.

RM: What mine did you work in over at Grantsville?

HH: They have different names for it - different companies came in there and they'd fiddle around and spend quite a bit of money and so on. Then when they ran out, other companies moved in there - so they had different names.

RM: Was it a big mine?

HH: Well, that was a big mine. It was still working in the '30s, when we first came over - people were still there.

RM: What was it called then?

HH: I think it was Alexander Brooklyn Mines Company . . .

RM: What other mines did you work in?

HH: Different prospects here and there. I worked over the mouth of Ophir Canyon - they built a mill in there.

RM: At the tungsten mine there?

HH: Yes, when tungsten went up.

RM: Who was that?

HH: Ed Gunther. He was a millionaire rice farmer down in California.

NH: And Homer worked 33 years at Basic in Gabbs.

RM: When did you start at Basic?

HH: In the early '50s - '52 or '53.

RM: What did you do there?

HH: I was a maintenance mechanic on the heavy equipment up there.

RM: I interviewed Ed. Alworth.

HH: Did he know me?

RM: Well, I didn't know you, then. I'm sure he knows you, yes.

HH: [laughs] Sure, he was one of my bosses over there.

RM: Did you work in the mill, or on the heavy-equipment?

HH: I did maintenance work everywhere, on different things - machinery and mills and . . .

RM: Did you work on the trucks and all that, too?

HH: Sometimes, yes. I did a lot of welding and cutting steel, operated cranes, loaders, backhoe, we started our own shovel, loaders, backhoe and road graders . . .

RM: Did you find the training that you had got at Stewart helpful in that?

HH: That's what I was talking about before; that's why it was so helpful, yes. Stewart had a road crew with all the equipment there, too. They'd train you on any subject you,wanted. Cats . . . the best Cat I ever ran was a D-9 Cat. They'll move a mountain. Not only that, but it ran so smooth, because the length of the machine is so long, and it's not wobbly like a little Cat. I could grade a road with it, just like a road grader, because they don't pivot like . . .

NH: And you worked at Mercury Mine at Ione, too, for 2 years.

RM: They were mining mercury there, weren't they?

HH: Yes.

RM: Did they retort it there?

HH: Yes. They had a 4-foot kiln and they burned the ore out of there.

RM: How many tons a day were they mining at that mine?

NH: Gosh, I wish I knew.

RM: Was it a lot or was it pretty small?

HH: It was quite a bit - a fair-sized operation for cinnabar. They'd burn it through their kiln, and all the vapor came out into condensers, and it condensed in these tubes. In the mornings the mercury was just running all over, filling up those little containers that they sat under.

RM: The flask?

HH: No, it's bigger than a flask. It's just a regular pipe, cut, and when you opened it just ran over, because those things wouldn't hold enough of it. I found the mother lode up there.

RM: Of mercury?

NH: Yes. Les Palmquist and I, an old man who was panning . . . he would pan the cinnabar, and estimate the amount it would make by looking at the inside of the pan. We found where the ore body was - the old mother lode.

RM: How big an ore body was it?

HH: Oh, it must've been 75 feet to 100 feet across.

RM: How tall was it?

HH: I don't know. It come down into the mountain, just like that, and thinned out like a funnel. Those people made millions out of there.

RM: That years were you there?

NH: He was there from '64 to '67, because he was at Basic before, and then when he left Basic he went to Ione and worked at that cinnabar mine and then they closed . . .

RM: You were at the Mercury Mine from '64 to '67 and at Basic from '52 to '64?

HH: Yes.

RM: Where did you live?

HH: Gabbs.

NH: We still have our trailer over in Gabbs - just a little one. He got hurt in February '86 and then they retired him.

RM: Oh. But in '67, you went back to Basic. Why did you quit Basic the first time?

HH: It was getting . . . a lot of my helpers wouldn't help. And they blamed the mechanic, naturally. The bosses would get after me for what they did and so on. I told them what was happening, but . . . so that was it - I didn't like it. But they kept calling me back because I can operate cranes and things.

RM: So you went back in '67 and worked there till '86? How did you get hurt over there?

HH: There go my helpers again. [chuckles] I had 2 helpers. We were unloading steel off of a pickup, and it had a banged up, rickety tailgate. The steel that we were unloading slid right over to the edge there. But we had already unloaded steel right here. I was standing [with my] back to the stuff we unloaded, and my helpers were there, ready to set this on the floor, and they left me holding that steel. I looked back, and the boss was standing there, looking at the parts they had unloaded there already. (That's why my helpers went over there.) When I looked back, the steel slipped. I should've just let it drop, but I tried to hold it. It was a freak accident. I wasn't tense enough to held it - I was still limber, not knowing that I . . . And I could feel . . . my collar bone just shrieked, you know - it made noise in there - crunch.

RM: Broken?

NH: Dislocated.

HH: Pulled out of its socket - yes. It pulled it out of the socket. My shoulder come out like that. And it hung there like it was on a string.

RM: Oh!

HH: I could put my finger in between there. So I held my arm like this, walked over to the boss, and I said, "That piece of steel dropped over there, and I had ahold of it, and it pulled my collarbone out, and my shoulder out." The office was right here, like that doorway. I walked in there and made out a report, and that's all it wrote.

NH: Then he got an infection in the joint - in the bone. He had 3 surgeries on it, and they put him on 6 weeks' penicillin - day and night, 100 ccs every 4 hours - for 42 days and 42 nights. On each subsequent surgery they did after that, they had to put him on a different type of antibiotic that had penicillin in it. And it gave him rheumatoid arthritis in all his joints.

HH: They swelled up like balloons, from my fingers clean down to my toes - my toes were sticking out like this. My knees swelled up like this - started gathering fluid in there. They started draining the fluid out . . .

NH: And they operated, because they thought the infection had spread. And they couldn't find . . .

RM: They couldn't find it?

NH: No. When the infection spread, it spread from the bone. They didn't get all of it, and it was spread in the bone and they had to go and dig a little more. Pretty soon it went into his chest and they had to go down into his chest and take out part of that flesh and stuff and just leave it hang open. By then, the consequence was that it gave him rheumatoid arthritis.

In turn, he was gone from work for one year - 12 consecutive months - and at that point you're automatically terminated. That's Basic's policy - in fine print. They would not let him have his last year of retirement, because they said he didn't work 1000 hours within that year Well, he was flat on his back in the hospital; he couldn't work 1000 hours. After 33 years, he was retired with 18 years. They wouldn't accept the first 13 years, because he had a break in service - the 3 years that he was in Ione. They wouldn't pick it up and make it retroactive.

But they were the ones who came after him to go back to work there. I mean, he didn't go asking for the job. We were living in Ione, and they kept coming back to Ione: "Come on, Homer, we need you; we need you." So he went back to work, with the stipulation . . . the union man said that they would get his first 13 years back. That would've made him have 14 years in, so it would be worth working towards his retirement. Well, the union man got killed in a car accident, out of Gabbs, and we didn't know that they didn't have it straightened out the way it was supposed to be. So when he retired, he had 18 years - actually, 19 years in, counting that last 12 months. But they gave him 18 years and that was it - after all those years.

RM: And he didn't get a full pension?

HH: No.

NH: He got half. And it's in little print. You know, when you go to talk to them, it's got little bitty print in there . . . it's in the book. The majority of the people aren't aware of it, unless they're in that position.

HH: I don't know how it would be if they had believed me when I told them that this pulled out of the socket in my shoulder. Not only that, but it pulled all the muscles loose in my head and my neck on down my back. But they couldn't recognize . . . They X-rayed.

RM: They couldn't see it in an X-ray?

NH: They sent him home - said he could go back to work in 3 days. HH: Oh, yes. And all this time, they X-rayed it - I don't know how many times. The first time, I think they X-rayed 7 different positions. They told me to go back to work. And I wasn't able to go to work. It'd start swelling; every day, it swelled bigger and bigger. Ten days later, it was like this, and I couldn't move; couldn't move my head. My head would fall back like that, and my muscles were all torn up in there. I'd pick up my head like this to get out of bed. If I couldn't, then she'd come help me a lot of times. It pulled my hair all out, picking away at it. Yes, I couldn't raise my head up.

I was real bad, and I told her, "Take me into the hospital. There's no other way." The doctors put a needle in there and tried to drain it, but it wasn't in there. It was solid flesh - just swelling. Then they said, 'Well, we'll have to operate on . . . ," then they looked in there and found out it was already infected and everything. And they cut all that flesh out and let the flesh grow back - left it out, you know. And there was a great big hole in there.

NH: A hole like this.

HH: And each time they'd scrape it, it took that much longer to heal. And every time, they went farther in - they'd scrape down in between my ribs and . . .

RM: Ohl

NH: Clear down - 'way down. Then they'd send him home. They finally put a Hickman catheter - that's a tube they put under the skin - that goes up under the collarbone, into the main artery that goes to your heart. The end of it sticks out here, and that way I could put medication in it. I'd give him a shot of his Vancomycin. Without being a trained nurse, you can't give shots in their skin, you know. So they put that Hickman catheter in there to give him his medication. That went on for 6 weeks.

HH: And it thinned my blood out so much that I had to take pills for building up my blood again.

NH: And it took his hearing, so now he's going to have to get a hearing aid. Vancomycin can cause all kinds of bad side effects. But the bone infection would've been mare deadly.

HH: But I don't think I'd be like this today if they would have believed me and opened it up, within a week, or within those several days, and found out that it was dislocated in there. They just kept X-raying it and they couldn't see it on there.

RM: How many Indians are there on the reservation now?

NH: Not too many, are there?

HH: The Smiths?

NH: There are 6 in the Smith family - Ed and Vickie Smith and their 4 children. And the next one down is Henick - you spoke to Henick before, didn't you?

RM: No.

NH: No? Pansy Weeks is his sister. But he's living in Fallon row. They're due to sell. Is Fenny still here? Kenny and Lynn Smith?

HH: Yes, they've still got the place there.

NH: And Rosemary Birchim and her 2 sons and daughter, and her married daughter, Penny.

HH: And their nother.

NH: Yes. And Penny Dyer and her husband, Pepsi. And then Ruth Rossi. And then Douglas Rossi - I'm not sure how many are in their family - 5 or 6.

HH: The old man.

NH: Yes. Bill Rossi and Virginia. And that's all till you get down here. Then there are Johnny Bob and his wife and 3 kids, and then the folks right down here.

RM: Off to the west of you.

NH: Yes, Ronnie Brady and Shirley and their 2 boys. And then there's Wayne Dyer and his wife and 3 children.

NH: Yes. And Gentry.

NH: John Gentry and his wife and one boy, and Noreen and her daughter. Then you go on down and there's Kevin Brady.

HH: No, one of our nieces is there - Priscilla Crucher. She just moved into that house there.

NH: And her 2 girls. And then up here there's Levi and Violet Artie [and Violet's son] Dar Meredith.

HH: Yes - and Demar's 2 boys.

NH: Demar's 2 boys and his wife. Well, she lives in Gabbs most of the time.

HH: And 2 daughters.

NH: Yes, they've got 4 children. And you've got Kevin Brady and his wife and 2 kids.

NH: And after Kevin there are no others. That's it for up this-away. And then Emma Bob, Maurice Frank, Henry Jackson, Leroy Brady and Verna and their son and his wife.

HH: Yes.

NH: And then Donald Brady and Roselyn.

RM: And that's it?

NH: Oh, there's Esther Bill - I saw Esther and Myron up here.

RM: And Levi, your brother, is the tribal chairman?

NH: And his daughter, Priscilla, is the tribal secretary now. His wife has some office job down there, too - they all work down at the tribal office.

RM: Are any people still following the old ways of the old religion, or anything like that?

HH: No.

NH: Not around here.

HH: No, they're [chuckles] a different generation, now.

RM: Are there any medicine men or anything like that?

HH: Are you kidding? That was done away with a long time ago. They don't do any beadwork . .

NH: Noreen George does beadwork.

HH: She might be the only one.

NH: Noreen George does beadwork. And Leroy is in one of the churches, but he likes to delve in Indian medicine and things. His mother used to be an Indian . . .

RM: Are there any traditional Indian ceremonies or anything like that?

HH: Nothing; no. We're just kids - younger people - here. [chuckles]

NH: One person you might like to talk to would be Bernice Hooper in Austin.

HH: Yes; my aunt.

NH: She's real talkative, and she has been around here for years and years and years.

RM: She's your aunt - so that'd put her up there in age?

HH: Yes, she's in her early 80s.

RM: Would she talk to me, do you think?

HH: I think so.

NH: She's raising her great-granddaughter, so she's still real active and on the ball.

RM: Could she tell me about some of the traditional beliefs and ways and things like that, do you think?

HH: She would. I must say, she would know more about that than . . .

RM: Do you think that she would tell me about some of the old ways?

HH: I think so.

NH: When you get to Austin, just call her. Tell her that you talked to Homer and he said to go see her. She's a very forward type person.

RM: Can you think of anything else we might want to mention here?

NH: I don't know, unless you want to talk about what a hard time the Indians have getting anything through the government, like getting water and getting them to put in dams. They just put in chintzy little things that flood out the first thing.

HH: Yes - all the diversion dams that they put in there washed out. Those diversion dams were made for flat country - the slope in this valley here is too much for them. When we have washouts, all the brush and stuff accumulates in front of those narrow gates, and that's it ¬then it goes around and tears them up. One year it tore the bridge out over here, and it washed all the diversion dams out.

RM: So a lot of water comes down the river . . .

NH: Once in a great while. That was the last year we had water. [chuckles] It washed the bridge out that year. We had to go way down to Elmer's and around all the way over to the base of the mountain to the old back road to get here. Nine miles one way from there on down, and back.

NH: We would have to leave one rig on this side and one rig on that side, and then walk across the foot bridge at the ranger station - down to this bridge.

HH: Down at the Forest Service they had a bridge that was going out, but it had boards still hanging on. We used to cross there, but they eventually burned it down. [chuckles]

NH: While we were still using it the Forest Service came and burned the bridge out.

HH: Yes, before they put this bridge up.

NH: Before they ever put this one in. So then we didn't have any way to get across.

RM: Are you a recognized reservation? I mean, is it a legal reservation, or does it have some other kind of semi-reservation status?

NH: What is this called? It's . . . assignment land?

HH: Assignment, yes.

NH: They call it the Yomba Shoshone Reservation now.

RM: On a lot of government things the Indian reservations have special status almost equivalent to what a state has.

NH: Yes, their own sovereignty with their awn boundaries . . .

RM: But you don't have that? Are you under the jurisdiction of the Nye County Sheriff?'

NH: Well, they have to get special permission to come on the reservation.

RM: Is that right?

NH: Remember, they had a thing down at the tribal hall, and they recognized . . . it used to be you had to get a BIA cop to come into the reservation. So they made an agreement where the police from Gabbs can come on the reservation.

RM: Where do you get your health care? Is there an Indian hospital nearby?

NH: At Fallon or Schurz. They used to have to all go to Schurz, then they opened the new one in Fallon. They have a van that runs once a week - sometimes twice a week - where they pick them up and take them into the doctor.

RM: Where do the kids go to school?

NH: Gabbs.

RM: They're bused over there?

HH: Yes.

NH: It makes a long day for little guys. They're on the bus by 7:00 and they get home at 4:30.

RM: That is long; yes.

NH: They have no kindergarten - kindergarten kids only go half a day, so most of the kids from the reservation don't get a chance to go to kindergarten, then they get over there they're having to fit in . . .

RM: So they're behind; yes. They teach a lot of things in kindergarten, now.

NH: I know they do.

RM: It's not like when I went to kindergarten - it was playtime, you know.

NH: A lot of the kids couldn't go to kindergarten, because they didn't have a place to go after school. I was trying to get them to set aside a roan with a teacher to monitor them, where they could let them take a nap or whatever until time for the his to leave. The school informed me that it was not a required grade, so they wouldn't do it.

RM: That's too bad.

NH: But a lot of the kids from last year and the year before that were held back, so now they're doing Chapter I in the afternoons, so that the kindergartners wind up going to school all day. They go to kindergarten in the morning, and Chapter I in the afternoon, and catch the his back. But that is one of the hardships - they don't have any Head Start programs or anything like that here. And the kids don't really socialize except with just their own family. Almost everybody's related, you know. Ripping them out of here and putting them in school . . . and the poor kids are just dumbfounded. It's really hard for them. But you can't get them to do anything.